Bernstein Network News. Find the latest news from our researchers regarding current research results, new research projects and initiatives as well as awards and prizes.

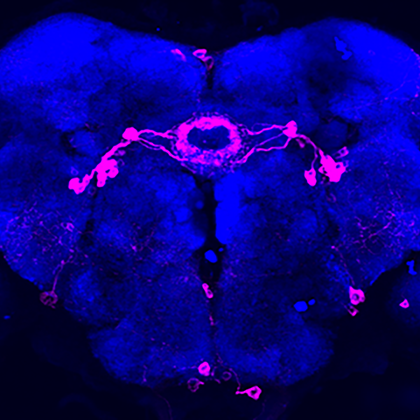

Charité study in Nature uncovers fundamental processes in the fly brain

Flies too need their sleep. In order to be able to react to dangers, however, they must not completely phase out the environment. Researchers at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin have now deciphered how the animal's brain produces this state. As they describe in the journal Nature*, the fly brain filters out visual information rhythmically during sleep – so that strong visual stimuli could still wake the animal up.

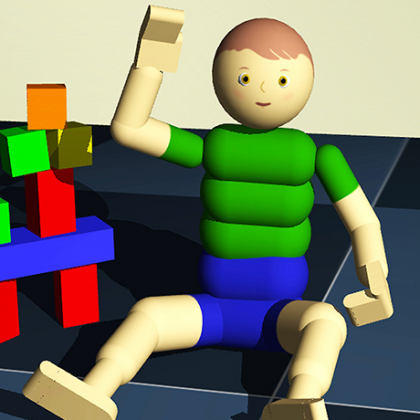

An artificial baby learns to speak – AI simulations help understand processes in the early childhood brain

A simulated child and a domestic environment like in a computer game: these are the research foundations of the group led by Prof. Jochen Triesch at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies (FIAS). It uses computer models to find out how we learn to see and understand—and how this could help improve machine learning.

“Nature Machine Intelligence” Study: Language models from Artificial Intelligence can predict how the human brain responds to visual stimuli

Large language models (LLMs) from the field of artificial intelligence can predict how the human brain responds to visual stimuli. This is shown in a new study published in Nature Machine Intelligence by Professor Adrien Doerig (Freie Universität Berlin) together with colleagues from Osnabrück University, University of Minnesota, and Université de Montréal, titled “High-Level Visual Representations in the Human Brain Are Aligned with Large Language Models.” For the study, the team of scientists used LLMs similar to those behind ChatGPT.

Sara A. Solla receives the Valentin Braitenberg Award for Computational Neuroscience 2025

Sara A. Solla receives this year’s Valentin Braitenberg Award for Computational Neuroscience for her “outstanding contributions to computational neuroscience over decades” (the award committee). The award ceremony will take place during the Bernstein Conference on September 30, 2025, in Frankfurt am Main.

Fending off cyberattacks in healthcare

rtificial intelligence (AI) is designed to make our health system even more efficient. Yet cyberattacks are capable not only of jeopardizing patient safety but also impairing medical devices and hindering the work of emergency responders. With the “SecureNeuroAI” project, researchers from the University of Bonn, University Hospital Bonn and FIZ Karlsruhe – the Leibniz Institute for Information Infrastructure are aiming to develop secure, AI-powered methods for detecting medical emergencies in real time using the example of epileptic seizures, although their findings should be applicable to many other areas. The Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) is providing almost €2.5 million in funding over a three-year period.

Smarter together: Large shoals of fish make better decisions

Free-living groups of fish recognize dangers more quickly and react more accurately the larger they are.

New center for brain research on the Garching campus

A new connectomics research center will be established on the TUM campus in Garching, which will focus on the comprehensive mapping and analysis of all neuronal connections in the brain. At the Center for Structural and Functional Connectomics (CSFC) at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), researchers from various disciplines will collaborate in such areas as state-of-the-art imaging technologies. The Joint Science Conference (GWK) has approved funding of around 69 million euros.

How jellyfish swim: HU study explains the interaction between neural networks and muscle activation

From the biophysical properties of individual cells to the movement of the entire body, a study at Humboldt-Universität explains how jellyfish control their locomotion.

AI that thinks like us – and could help explain how we think

Researchers at Helmholtz Munich have developed an artificial intelligence model that can simulate human behavior with remarkable accuracy. The language model, called Centaur, was trained on more than ten million decisions from psychological experiments – and makes decisions in ways that closely resemble those of real people. This opens new avenues for understanding human cognition and improving psychological theories.

Looking for inspiration? Try a short nap!

Sleep increases the ability to creatively solve problems. That was the result of a study of 90 subjects at the University of Hamburg. Indeed, it is possible to use the levels of brain activity measured during sleep to predict the likelihood of a lightbulb moment after waking. The results are currently being published in the PLoS Biology journal.