Suspect arrested, investigation moves to next round

It is probably one of the most extensive investigative files in the history of science. The case has been unsolved for centuries. The reporting, at first heavily influenced by speculation and philosophical deliberations, has had tangible and convincing successes to report in recent decades. The investigators' methods are improving, and the circle of suspects is shrinking. The noose is tightening. A new episode in this whodunit has just been released.

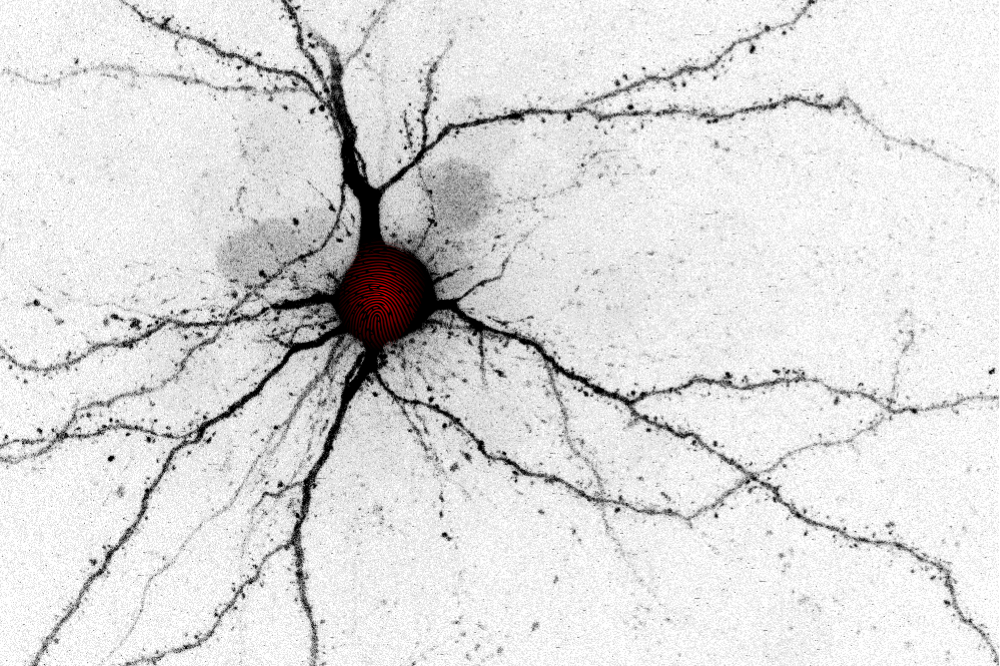

During learning, neurons change the role they play in a network. We found that imposing some mild exercising on neurons by external stimulation can trigger a rewiring of the network. The observed changes follow a very specific temporal profile that was first seen in computer simulations. Image: Han Lu & Stefan Rotter

Bernstein members involved: Julia Gallinaro & Stefan Rotter

It has been clear for a long time: Brains change their inner workings and their material structure to reflect new experiences and changing circumstances. This plasticity gives us advantages and is often enough essential for survival. But how exactly does it work? For the last hundred years or so, we have been guessing where the scene of the crime lies: the nerve cells and the social networks they form with their peers. Perpetrator profiling suggests that interception of communications between cells could shed new light on this case. A search for clues in sea slugs and cell cultures convicts electro-chemical signal transmission at synapses as accomplices. But the search also reveals limitations, much to the chagrin of investigators. Virtual reconstructions of the crime scene make it clear that the prevailing theory has gaps. A thick fog hangs in particular over a possible contribution of changes in the wiring of the networks. Some witness statements don’t fit the picture at all. But who is the Great Unknown? Who is pulling the strings in the brain?

Inspector Han Lu, equipped with a keen sense for important twists in unsolved cases, now presents her investigative findings. Her four colleagues in the international team of investigators are initially puzzled by her unconventional methods, but then let her have her way. Fresh from university, she has the latest methods in her suitcase. Inspired by computer simulations and the possibilities of optogenetic methods, she goes on the attack: What if neurons not only change the electro-chemical messages they send to others, but even reorganize their entire social network if it seems opportune? But would a suspicious rewiring of the network take place silently, without activating the alarm system? She uses computer simulations to create a precise perpetrator profile. Then she employs optogenetic stimulation in mice to reconstruct the exact chronology of the crime under controlled conditions. Finally, she compares the measured changes in the animals’ brains with the previously created offender profile from the computer simulations. The result of this, based on a unique combination of investigative methods, is that the fingerprint fits and a plausible motive has been found!

Has the Great Unknown thus been identified? Can the new evidence also convince her colleagues from other task forces? Will they now possibly find further independent evidence that proves an important role for regulated structural changes? How exactly would those work together with the accomplices who have already been apprehended? This is enough material for many more episodes in the thriller about how the brain learns.