Can you hear what I say?

Neuroscientists at TU Dresden were able to prove that speech recognition in humans begins in the sensory pathways from the ear to the cerebral cortex and not, as previously assumed, exclusively in the cerebral cortex itself.

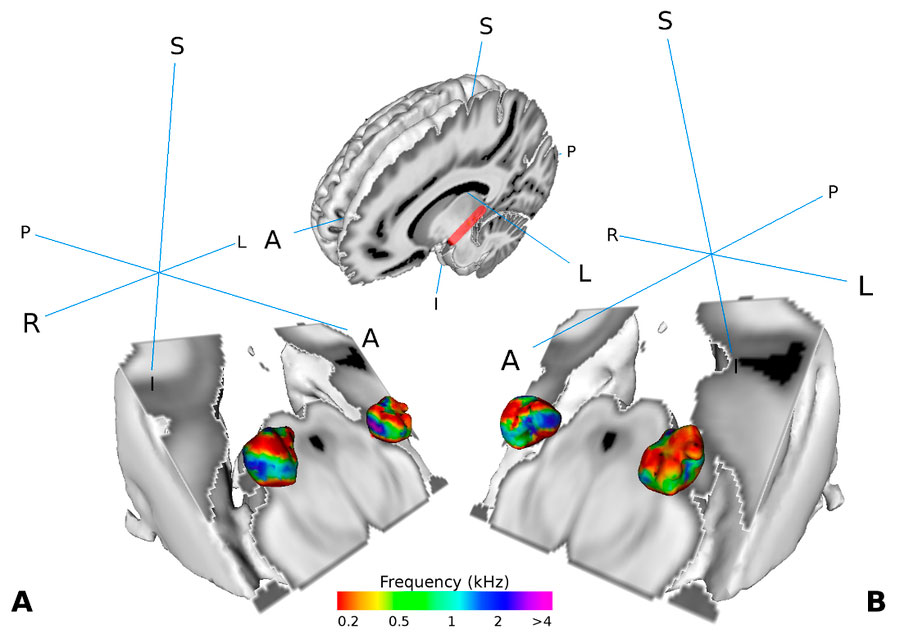

Visualization of the medial geniculate body (MGB) in the brain of human test persons. The MGB is part of the auditory pathway. It is organized in such a way that certain sections represent certain sound frequencies. The study shows that the part of the MGB that transmits information from the ear to the cerebral cortex is actively involved in human speech recognition. © Mihai et al. 2019, CC-BY license

/TU Dresden/ In many households, it is impossible to imagine life without language assistants – they switch devices on or off, report on news from all over the world or know what the weather will be like tomorrow. The speech recognition of these systems is mostly based on machine learning, a branch of artificial intelligence. The machine generates its knowledge from recurring patterns of data. In recent years, the use of artificial neural networks has largely improved computer-based speech recognition.

For neuroscientist Professor Katharina von Kriegstein from TU Dresden, however, the human brain remains the “most admirable speech processing machine.” “It works much better than computer-based speech processing and will probably continue to do so for a long time to come,” comments Professor von Kriegstein, “because the exact processes of speech processing in the brain are still largely unknown.”

In a recent study, the neuroscientist from Dresden and her team discovered another building block in the mystery of human speech processing. In the study, 33 test persons were examined using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The test persons received speech signals from different speakers. They were asked to perform a speech task or a control task for voice recognition in random order. The team of scientists recorded the brain activity of the test persons during the experiment using MRI. The evaluation of the recordings showed that a structure in the left auditory pathway – the ventral medial geniculate body, (vMGB) – has particularly high activity when the test persons perform a speech task (in contrast to the control task) and when the test persons are particularly good at recognizing speech.

Previously, it was assumed that all auditory information was equally transmitted via the auditory pathways from the ear to the cerebral cortex. The current recordings of the increased activity of the vMGB show that the processing of the auditory information begins before the auditory pathways reach the cerebral cortex. Katharina von Kriegstein explains the results as follows: “For some time now, we have had the first indications that the auditory pathways are more specialized in speech than previously assumed. This study shows that this is indeed the case: The part of the vMGB that transports information from the ear to the cerebral cortex processes auditory information differently when speech is to be recognized than when other components of communication signals are to be recognized, such as the speaker’s voice for example.”

The recognition of auditory speech is of extreme importance for interpersonal communication. Understanding the underlying neuronal processes will not only be important for the further development of computer-based speech recognition.

These new results may also have relevance for some of the symptoms of developmental dyslexia. It is known that the left MGB functions differently in dyslexic persons than in others. A specialization of the left MGB in speech may explain why dyslexic people often have difficulty understanding speech signals in noisy environments (such as restaurants). Katharina von Kriegstein and her team are now going to carry out further studies in order to scientifically prove these indications. (Text: TU Dresden)

Original publication

“Modulation of tonotopic ventral MGB is behaviorally relevant for speech recognition” Paul Glad Mihai, Michelle Moerel, Federico de Martino, Robert Trampel, Stefan Kiebel, Katharina von Kriegstein: eLife 2019;8:e44837 doi: 10.7554/eLife.44837